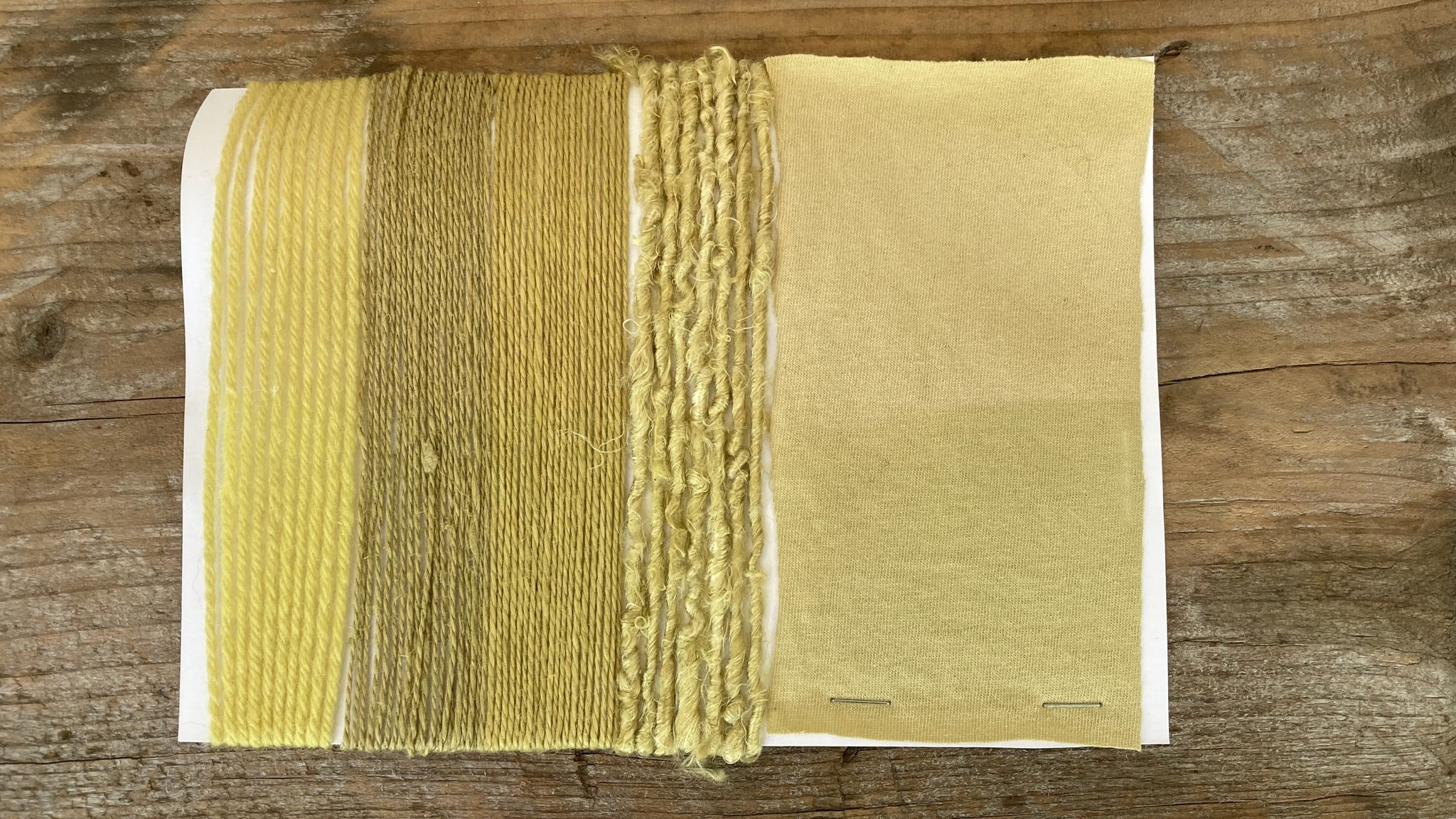

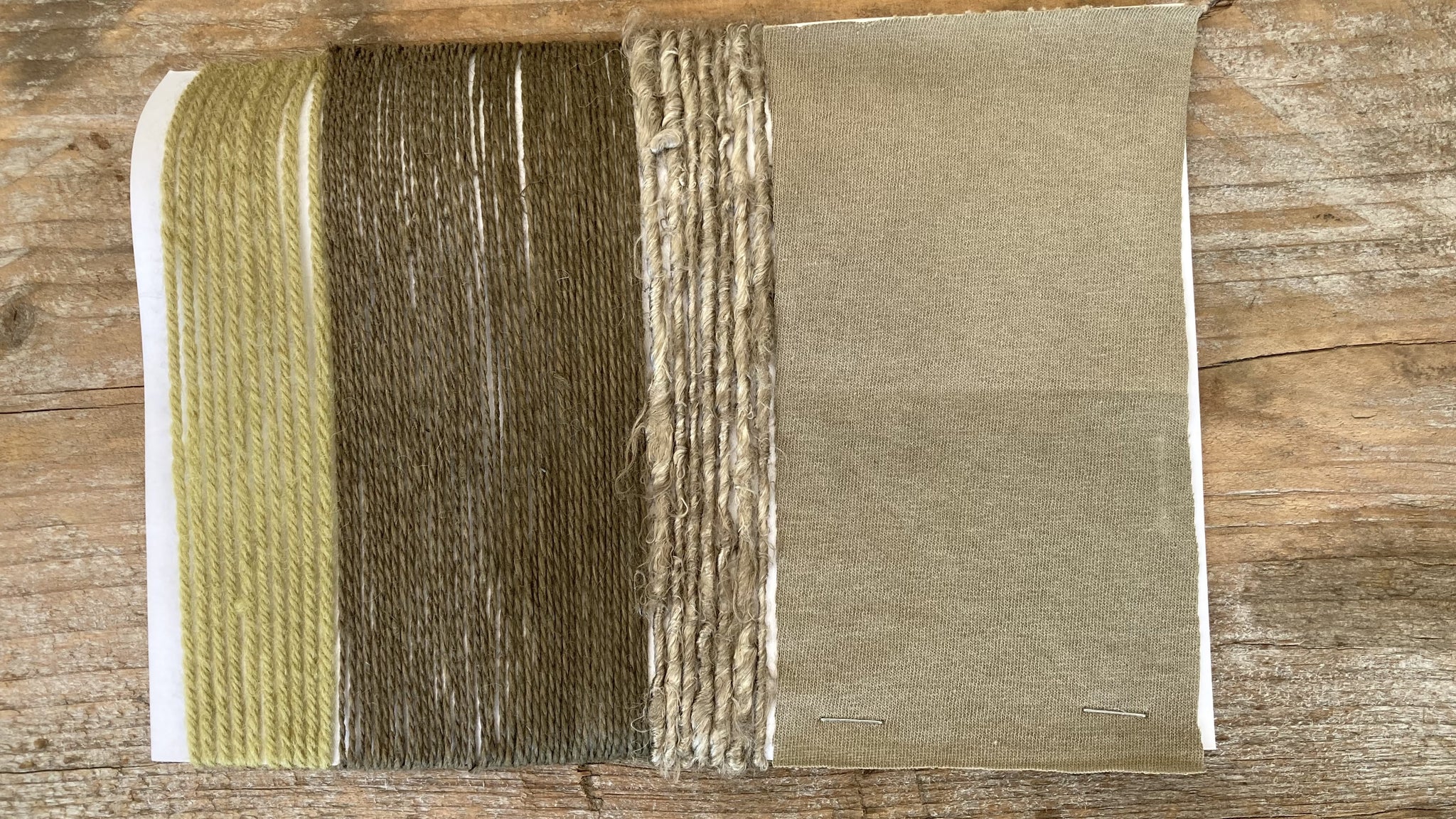

Final dye results

Sharing the hedgerow with rosehips and ripening sloes, flowering yarrow is a sign of approaching autumn. Sometimes referred to as Common Yarrow, it’s a perennial plant in the family Asteraceae, with many native and cultivated species.

Originally found in Eurasia and North America it has long been used in traditional medicine, as its many folk names suggest; bloodwort, soldier’s woundwort and nosebleed to name just a few. The word ‘Achillea’ derives from the mythological Greek warrior, Achillies, who is said to have treated his wounded soldiers with the plant.

Yarrow was cultivated in medieval herb gardens for culinary as well as medicinal purposes, but evidence of this bitter herb goes as far back as Neanderthal gravesites. The heady, astringent vapour rising from a pot of heating yarrow certainly suggests it must be good for something, and indeed it is still widely used in herbal medicine today.

Yarrow growing on a verge

I had to go quite a long way to find enough yarrow for my dye pot because, flowering late summer, many verges had been cut. Yarrow only grows to about a foot tall, so tends to favour the edge of green areas where it doesn’t have to compete with taller plants, making it particularly vulnerable to eager cutting back.

Yarrow in a basket with rosehips and sloes

After gathering plant material for the dye bath it’s important to leave it outside for a couple of hours, to give the insect life a chance to move on. Flying insects depart swiftly, but creepy crawlies are sometimes reluctant to leave. Giving the dyestuff a bit of a shake usually works!

Raw fibres

For this natural dyeing project I’m using a skein of naturally white Bluefaced Leicester wool. Wool is an animal (protein) fibre.

I’m also using four plant, (cellulose) fibres These are: a skein of natural linen, a skein of bleached linen, a skein of natural banana yarn and a square of bleached cotton.

NB: Be sure to weigh your dyestuff before soaking it, so you know what ratio of mordant, dye etc to use for best results.

Weighing the dyestuff

For many natural dyeing projects, equal weights of fibre and dyestuff will give a good colour, ie 100% weight of fibre (WOF). As my dry samples yarns weighed approximately 100g, I planned to use 100g of Yarrow tops. However, I then came across another patch of Yarrow and couldn’t resist adding a few more heads to the dye pot, so I probably used about 150g (150% WOF) of dyestuff in this dye bath.

Steeping the dyestuff

To extract the most colour from your dyestuff it’s a good idea to pour kettle-hot water over the plant material, to soften it up, and then to leave it to cool and to steep overnight.

Heating the dyestuff

The next morning the now softened leaves had already imparted some colour to the water and the dye bath was heated slowly to 80C, a gentle simmer, and held at that heat for about an hour.

A thermometer is helpful, but if you haven’t got one just keep an eye on the dye bath and reduce the heat as soon as the first small bubbles begin to rise to the surface.

Overheating natural dyes tends to dull the colours. I used an electric hob and removed the dye pot to a heatproof mat from time to time to regulate the temperature. A gas hob is easier to control.

Once the dye bath had brewed for an hour it was removed from the heat and left to cool and steep overnight.

Straining the dyestuff

When the dyestuff has cooled the solution can be strained into a clean bowl using a sieve, lined with a muslin cloth. Give the muslin a good squeeze to extract as much colour as possible. These spent Yarrow flowers then went straight onto the compost heap, but in the case of some dyestuffs (eg Correopsis) there is often enough colour left to be worth extracting in a second dye bath.

Be sure to rinse out the dye pot before returning the strained solution, so you have a good clean, clear dye bath without any bits that may get caught up In the fibres.

Entering fibres into the dyebath

Make sure there is enough solution in the dye bath to allow the fibres to move freely. Top up with more water if necessary. This will not dilute the dye bath as the fibres will take up the dye particles available regardless of the amount of water.

When entering fibres into a natural dye bath it’s important to put them all in at once. If you add one lot of fibres, and then some more, you may find that the first lot of fibres entered have taken up more than their fair share of dye particles, and the fibres entered a short time later will be paler.

It’s easier to get even dye results on yarns than it is on pieces of fabric, which tend to fold over on themselves. The folds and creases dye unevenly (see blog Natural Dyeing With Nettles) so when entering fabric into a dye bath try and minimize these. With larger pieces of fabric it’s necessary to keep working the fabric around in the dye bath, and lifting it in and out to make sure the dye is reaching all surfaces evenly.

Heating the dye bath

The dye bath was heated to 80C and held at this temperature for about an hour, the fibres being gently moved around the pot from time to time to ensure an even dye result.

Once the dye bath had brewed for an hour it was removed from the heat and left to cool and steep overnight. However, once a dye bath has cooled, if you feel you have a colour you’re happy with, you may decide not to leave the fibres in overnight. It is a question of ‘capturing’ the best colour, bearing in mind that fibres will be several shades lighter once they’ve been washed and dried, than they were as they emerged from the dye bath.

Hanging the fibres to dry

Remove the fibres from the dye bath and hang them to dry without washing them. This allows he fibres to absorb as much of the dye as possible. Washing them immediately risks losing some of the precious dye.

Washing the fibres

Once dry the fibres should be washed well in warm water with a neutral detergent …..

Rinsing the fibres

….. and then rinsed well in several changes of cold water, until the water runs clear – or almost.

Making an iron modifying bath

I prepared a double lot of fibres so I could ‘modify’ one lot with iron, which will always deepen or ‘sadden’ the tone of natural dyes. ‘Modifying’ fibres after they’ve been dyed is a way of extending the colour range of a dye bath. This can be done using various solutions (see elkatextiles.co.uk) but iron is the most commonly used by natural dyers.

Iron stains everything so you need separate pots and utensils to create an iron modifying bath. You can make your own iron water (ferrous acetate) with a mixture of water, vinegar and some rusty pieces of metal (see elkatextiles.co.uk) or from craft suppliers you can buy some ferrous sulphate, which I’m using here.

To make an effective iron modifying bath you only need a pinch of ferrous sulphate, dissolved well in warm water, and added to enough warm water to allow the fibres to move freely. 1% WOF is a good gauge.

The iron bath

Fibres will change colour quickly in an iron bath, so keep an eye on the process and remove the fibres as soon as you have the colour you want – allowing for the fact that they will darken a little more after being removed from the iron bath.

Iron can be damaging to fibres, particularly animal fibres such as wool, so don’t leave them in the iron bath for long. Modifying with iron improves the colourfast quality of natural dyes, and iron can also be used as a mordant, before dyeing.

Hanging the modified fibres to dry

The fibres should then be washed and rinsed as above.

Final results

I was surprised to see just how much colour came from the small, delicate, white Yarrow flower heads. The yellows, while not as vibrant as Weld or Goldenrod, are gently pretty. The different fibres have dyed to very different colours and the iron modifier has extended the colour range into soft green and browns. It’s nice to see the banana yarns have kept their attractive lustre. I might try 200% WOF next time.

LIGHTFAST TESTING

These lightfast testers were left on a south-facing window sill for eight weeks; October and November. The bottom half of the card was kept out of the light while the top half was exposed. As always, the samples modified with iron have held their colour well, but the non-modified samples have proved to be equally resistent to the light - though I think the colour may have deteriorated generally.

References

gardenerspath.com

theoldie.co.uk

Jenny Dean (2010) Wild Colour Octopus Publishing Group

Boutrup and Ellis (2018) The Art and Science of Natural Dyes Schiffer Publishing Limited

www.wikipedia.org